Do you remember that xkcd strip where an atomic bomb requires a valid tar command to disarm itself? Either way in this post you will learn about GNU tar features you are already familiar with, but also few details you maybe don’t have any idea about.

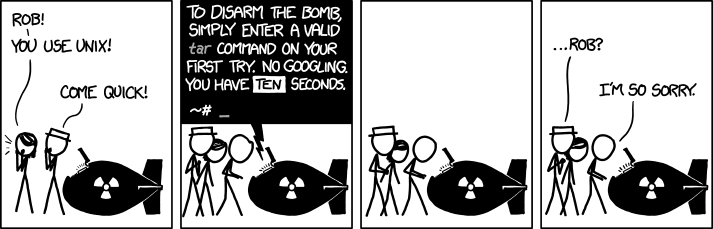

Let’s revisit the strip (after all, it was published few years ago already):

By Randall Munroe, xkcd.com, CC BY-NC 2.5

First of all I have to note that I consider this to be little far fetched. And that’s ok, it’s a joke after all, but tar doesn’t belong to group of tools for which I have to look up it’s command line options often. Maybe a better example would be some of less often used git scenarios, but compared to tar, it lacks it’s bombastic connections (see a tar bomb or Tsar bomb), which makes it little unsuitable for the purposes of this joke.

That said I have to admit that when I was using extract script from

archlinux wiki

instead of working with tools like tar or unzip directly, I wasn’t always

able to use tar without looking into a man page or a google search either.

But that was a long time ago, and in the meantime I learned that it isn’t that

hard after all.

In most cases it’s enough for me to know that tar xf file.tar.gz extracts

file(s) from a tarball (where xf is extract file), and that

tar caf file.tar.gz file compresses given file into new tarball (where

caf I remember as create archive file, and compression type

of the new tarball is chosen according to it’s suffix).

I should probably note that even thought there is GNU

tar installed as a default tar

implementation on most machines I have access to, in all

previous examples I used BSD style command line options, which I prefer to use

with tar for some reason.

Maybe it’s because I would have to type one additional character compared to unix style:

$ tar -caf file.tar.gz fileAnd for casual command line usage, comparison with GNU style doesn’t make sense:

$ tar --create --auto-compress --file file.tar.gz fileYou can notice that the a option doesn’t actually stand for archive

as I suggested above, but that is how I recall it.

That said, the real reason for my preference of tar BSD options could be much easier to explain. I most likely use tar this way because I saw it somewhere long time ago, and since then I used it over and over again many times without thinking much about it. And I guess that this, maybe little random inertia, is not only my case.

When you perform internet search for examples of tar usage, you can run into

various single letter tar options like z or j, which define type of used

compression (z means gzip, j stands for bzip2). And I’m not sure you

will be happy to learn that for xz compression, corresponding single letter

option is J. And since we are discussing GNU tar, there is long option --xz

as well. Moreover since GNU tar already run out of single letter options, new

compression types are being added with long GNU style option only.

And yet, the auto compress option discussed above is available in GNU tar for

almost 10 years already (since version 1.20 released on

2008-04-14). This is

enough time for this feature to land even in stable and conservative GNU/Linux

distributions like RHEL

6

or Debian oldstable.

On the other hand good luck with trying this GNU feature on non GNU systems such as OpenBSD:

$ tar caf archive.tar.gz random.c file1.c

tar: unknown option a

usage: tar {crtux}[014578befHhjLmNOoPpqsvwXZz]

[blocking-factor | archive | replstr] [-C directory] [-I file]

[file ...]

tar {-crtux} [-014578eHhjLmNOoPpqvwXZz] [-b blocking-factor]

[-C directory] [-f archive] [-I file] [-s replstr] [file ...]Which brings us to the possibility that the xkcd strip is also making fun of incompatibilities among various tar implementations (such as the mentioned difference between GNU and OpenBSD). Why couldn’t the bomb be running some extra old distro, FreeBSD or even Solaris? But in this blog post, I’m not going to dig into this topic deeper. Not just tar but all classic unix tools suffers from this problem to some extent after all.

But let’s check one more GNU tar option which is worth mentioning: t or

--list, which lists files in given tar archive:

$ tar tf passthrough.tar.xz

Makefile

passthrough.1

passthrough.cAnd with that we completed the list of tar command line options I remember and I’m able to casually use. For anything else, I have to open a man page or documentation, which can sometimes surprise me because of sheer number of features implemented in GNU tar.

For example I recently wanted to generate sha1 checksum of all files in a

tarball without extracting all its files at once (which is obviously not

necessary for this purpose, and in my case I didn’t even have enough free space

available for that) and it turned out that GNU tar allows to specify command

which will receive extracted content of each file on stdout via option

--to-command. So I wrote the following wrapper script ~/bin/tar-sha1-t.sh:

#!/bin/bash

# see also: man tar, https://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/303667/

echo -n $(sha1sum) | sed 's/ .*$//'

echo " $TAR_FILENAME"And generated the sha1 checksum list without saving single extracted file on disk like this:

$ tar xf foo.tar.gz --to-command=~/bin/tar-sha1-t.sh

384dcab2b0e67e940406d1bbfd1b083c61319ce4 foobar.png

e1c272d5abe7d339c4047d76294e7400c31e63b4 READMEOr you can just run into unfamiliar feature randomly without even trying. For example, I was bit confused at first when I noticed that tar failed with error after executing the following command:

$ tar caf ccpp-2018-03-03-23:10:55-3667.tar.gz ccpp-2018-03-03-23:10:55-3667

tar (child): Cannot connect to ccpp-2018-03-03-23: resolve failed

tar: Child returned status 128

tar: Error is not recoverable: exiting nowWhy did tar try to connect somewhere over network just based on a tarbal filename? But after some searching it turned out that:

An archive name that has a colon in it specifies a file or device on a remote machine. The part before the colon is taken as the machine name or IP address, and the part after it as the file or device pathname, e.g.:

–file=remotehost:/dev/sr0

An optional username can be prefixed to the hostname, placing a @ sign between them.

And if you don’t like this, GNU tar provides the following option:

–force-local

Archive file is local even if it has a colon.

So that the following command will work just fine:

$ tar --force-local -caf ccpp-2018-03-03-23:10:55-3667.tar.gz ccpp-2018-03-03-23:10:55-3667But if you try to use tarball with such name later and forgot about the colon there, you will fail on it again:

$ tar tf ccpp-2018-03-03-23\:10\:55-3667.tar.gz

tar: Cannot connect to ccpp-2018-03-03-23: resolve failedThis made me wonder when was the feature added and why. So I checked the NEWS

file and found this:

Version 1.11 - Michael Bushnell, 1992-09.

Version 1.10.16 - 1992-07.

Version 1.10.15 - 1992-06.

Version 1.10.14 - 1992-05.

Version 1.10.13 - 1992-01.

* Remote archive names no longer have to be in /dev: any file with a

':' is interpreted as remote. If new option --force-local is given,

then even archive files with a ':' are considered local.So it’s there since 1992, which means I haven’t ever used GNU tar without this feature, and yet was not aware of it until now.

And I have to admit that I don’t understand reasoning behind this design:

wouldn’t be better to have an option like --remote-file instead, which would

enable the feature explicitly? But maybe I’m missing some historical

perspective. Needless to say that OpenBSD tar doesn’t implement this.

I asked this question on help-tar

list,

which gave me some perspective on usefulness of the feature, but unfortunately

nobody provided more context about the choice of having it enabled by default

yet.

And there is one aspect of the feature worth checking. What is the protocol tar uses to connect to the remote machine? Looking in the docs again we see:

By default, the remote host is accessed via the rsh(1) command. Nowadays it is common to use ssh(1) instead.

So nowadays GNU tar will just try to connect to a remote host via ssh, which we can demonstrate on properly named tarball:

$ tar tf localhost:foo.tar.gz

The authenticity of host 'localhost (::1)' can't be established.

ECDSA key fingerprint is SHA256:TgLgqk9xkWb2oGtBRgk1vKPvWzbgdkp0InR0PZHXnbQ.

ECDSA key fingerprint is MD5:48:16:9c:eb:b8:22:0f:ab:22:b4:71:a5:3e:54:2c:7f.

Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no)?At this point we may be wondering whether such behaviour isn’t weird enough to be considered as a security problem to some degree.

For example, we could come up with a scenario when an attacker provides a tarball to a victim and prepares another tarball on a remote system with a different content, which the victim would download and extract instead of actual content of the provided tarball without realizing it. Assuming that the victim wouldn’t find suspicious that there is a domain name in tarball name (which points out directly to the attacker), that the attacker knows a login name of the victim and has a public ssh key of the victim and that victim either doesn’t use any passphrase for the key, or the key is loaded in ssh agent of the victim when tarball extraction attempt happens, and last but not least that the ssh fingerprint of the attacker’s remote system specified in the tarball is already in known host file of the victim, or even better, if the victim has ssh fingerprint verification disabled, at least for the hostname of the attacker.

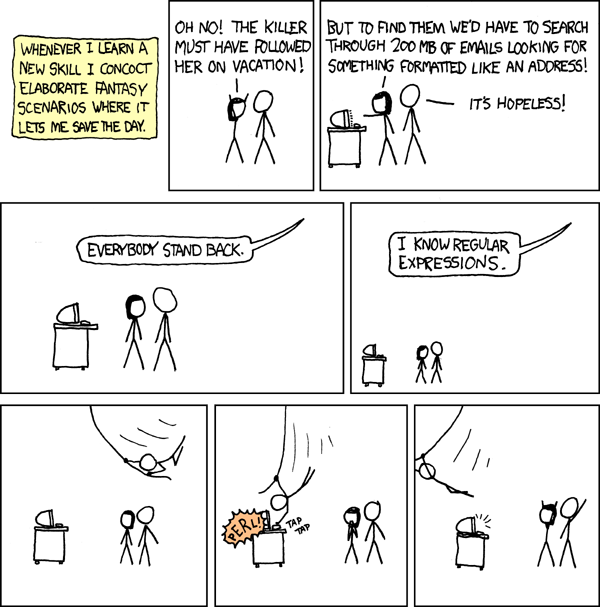

Some of these requirements could be simplified by configuring attacker’s sshd to accept any login name with any key … but at that point I find myself in another xkcd comics, just replace the problem solvable by a perl hack with the previous section about gnu tar, it’s roughly on a similar level of craziness.

By Randall Munroe, xkcd.com, / CC BY-NC 2.5

Nevertheless, from a technical perspective, it will realy work under all these assumptions. Let’s prepare one good and one bad file in a temporary location:

$ cd ~/tmp

$ touch good-file bad-fileThen we compress the bad file as bad.tar.gz and move it to home directory:

$ tar caf bad.tar.gz bad-file

$ mv bad.tar.gz ~Then we compress the good file as localhost:bad.tar.gz:

$ tar --force-local -caf localhost:bad.tar.gz good-fileSo now, when we ask for content of localhost:bad.tar.gz archive, we get a

different answer with and without --force-local option:

$ tar tf localhost:bad.tar.gz

bad-file

$ tar --force-local -tf localhost:bad.tar.gz

good-fileAn inverted use case, when you suggest a proper tarball name to a victim so that the victim will end up uploading content of their tarball to a server under your control is possible as well, but it’s still as crazy and impractical as the previous case.

In the end, this isn’t suitable even as April fools’ day joke. Maybe if someone is extra lucky when writing a shell script using tar while accepting untrusted tarball input. But I’m not sure how likely something like that is :)

If you find topic of this post interesting, maybe you will learn something more useful or surprising after a brief listing through GNU tar manual.